Faithless Fidel?

The picture you see is just short of fifty years old. I cut it from a Catholic magazine in 1960 because it made an impression on me of inhumanity expressing itself that I found hard to shake off. Looking at it from time to time in the interim has reinforced that impression and I have waited nearly fifty years to use it.

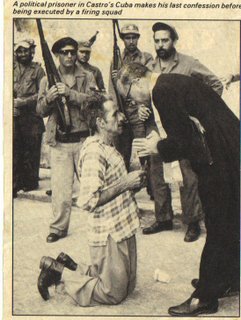

The picture you see is just short of fifty years old. I cut it from a Catholic magazine in 1960 because it made an impression on me of inhumanity expressing itself that I found hard to shake off. Looking at it from time to time in the interim has reinforced that impression and I have waited nearly fifty years to use it. It shows the confession and reconciliation, prior to execution, of a political prisoner in Fidel Castro’s Cuba. Note that the kneeling man carries a cross in his hands and it cannot be said that his executioners are going about their work unwillingly according to some of their expressions. The picture expresses a moment frozen in time that shows a nameless man facing death; the last century knows a lot about that. Such loneliness as the unknown was experiencing is hard to imagine or to graft oneself onto. Yet he was not alone.

The picture’s three elements, politics, revolution and Church, symbolise the course of the Cuban revolution led by Fidel Castro. Revolutionaries with guns in their hands waiting to delete their political enemies, waiting as it later turned out to delete the Church, all in the name of revolution. To outside eyes at that time Castro and his group in the mountains seemed to epitomise a revolution that would sweep away dictatorship and corruption. His bulletins did not lack the rhetoric for which he later became famous and much later became boring. Somehow they exuded enthusiasm and dedication. Photos of him and his companions, with their chaplain, in the mountains in 1959 gave a lift to the spirit and an optimism that was hard to explain. It was all a sham.

Time told the true story. Fidel’s true colours were nailed to the Cuban mast at the same time as he and his revolution-minded companions nailed Cuba to its own particular cross. His disclosure of his Marxist-Leninist sympathies in 1961 and his subsequent declaration that Cuba was to be a communist country was soon succeeded by active persecution of the Church of Cuba, in the archetypal way that communist takeovers have. Nothing got better over the next half century for the Cuban who would worship God, rather than Castro’s pantheon of atheists like Stalin or Marx. Fidel after all was soon to declare Cuba an atheist state, and predictably, that religion is the opiate of the masses. Schools and churches were closed, priests exiled, the Church was denied access to the media and limits were placed upon the clergy. Some alleviation, but not much, came with a visit by Pope John Paul.

Some day, psycho-historians will make an in-depth study of the reasons why dictators who have been brought up and educated as Catholics perform the volte-face so typical of them and start to persecute religion, particularly the Catholic belief. Fidel, again predictably, is no exception. Son of a landowner, he was educated in various private Catholic boarding schools, and finished his secondary education in a Jesuit school in Belen. After graduation as a lawyer, he took up active politics and revolution. In 1953, he led an attack on an army post, was captured and sentenced to 15 years in prison. Released after two years, rumours have persisted that the Archbishop of Havana interceded on his behalf. The rest is history; the kind of history that has trapped Cubans in a 1950’s social timewarp and shackled to a 19th century clapped-out and outdated political philosophy.

Reports of Fidel’s demise have been exaggerated this time, but what is true is that like all of us, he will die one day. I hope that he will be granted the opportunity of repentance, a gift that his actions have denied to many Cubans. There are reports that he has asked liberation theologian Leonardo Boff to be with him at his bedside when his time comes – always a good sign that something remains there. The bishops of Cuba issued a pastoral letter that called on catholics to pray for Fidel in his illness – an example of forgiveness in the face of everything to which we should all aspire.

When he does die, I hope that he will not join his hatchet man Che Guevara on the T-shirts of the world. Che allegedly is the poster boy of revolution for the young and has achieved the doubtful distinction of cotton immortality. I hope too that we will be spared the eulogies and encomia that are inevitable accompaniments to the demise of national figures today regardless of the depredations they have practised on their fellow men and women. Fidel made the mistake of not getting killed early on, leaving him the opportunity to get stuck more and more in the mire of his failed social and political philosophies. His place in history will be in the memories of the dwindling number of failed and defunct revolutionaries of the 60’s whose enthusiasm for change at any price has brought about countless hardships to millions and who are irrevocably in denial.

I shall continue to treasure my now slightly tattered picture, to remind me that if we fail to learn from history, we will be condemned to relive it.